“Clean” broke out. Like “pumping iron” in the ’70s, “juice” in the ’80s, and “swole” and “diesel” this century—and let’s not forget the most muscular pose, struck by athletes after touchdowns, dunks, or almost any big play in almost any sport—“eating clean” was a bodybuilding thing that went mainstream. What makes this one different is the wider public changed its meaning, sparking a backlash. How did “clean” grow too big for its own good?

CLEAN EATING: THE BREAKOUT

Subcultures have their own lingo, separating those who’re in from those who’re out. Sometime in the mid-’90s, I added “clean” to my vocabulary as a verb or adjective meaning to eat like a dieting bodybuilder (essentially high-protein, low-carb) and soon thereafter realized no one outside my swole tribe knew what I meant when I used the word to refer to meals. You mean washed food?

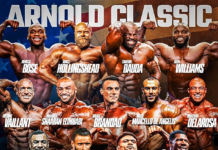

A decade or so later, “clean” made a jailbreak. It began with the best-selling The Eat-Clean Diet in 2007, the first of a popular series of Eat-Clean books by Tosca Reno, who was very familiar with the bodybuilding subculture. Her husband was the late Robert Kennedy, publisher of MuscleMag, as well as Oxygen, Reps!, and, eventually—but of course—Clean Eating magazine, which is still in print today.

Tosca Reno carried over much of the bodybuilding definition: a focus on lean protein and complex carbs (as well as weight-training and supplements), but she also prophesized for whole organic foods, writing things like this: “We live in a chemical soup experiment. Processed foods have undermined our health, especially sugars, which are deadly anti-foods that have no place in our body.”

There it was—the redefining. Since then, “clean” has gone from hardcore fitness to softcore wellness, a smart marketing strategy, for sure, because there’s a lot more people in the latter category. Cookbooks, plans, podcasts, YouTube videos, more every year. It’s become the catchall term (#eatclean) for any and all healthy or natural nutrition.

How mainstream is it? Panera Bread adopted the slogan “100% of our food is 100% clean.” The National Heart Association released an infographic of its healthy eating tips with the title: “So You Want to Eat Clean?” There’s even an Eating Clean for Dummies book, which is a sure sign “clean” has reached such a level of saturation this genie can never fit back in the protein shaker.

CLEAN EATING: THE BACKLASH

The problem with going so big is the term doesn’t just stretch to include organic everything. It also includes a lot of quackery and dubious claims. And therein lies the backlash, well, that and the fact that it’s perceived as elitist: farmer’s market over supermarket. (A 2015 Consumer Reports study found organic foods cost, on average, 47% more than non-organic.) Vice published the viral hit “Eating Clean is Useless”; Good Housekeeping upped the ante with “Why Clean Eating is Total B.S.” (Seems like those titles should’ve been reversed. Who knew Good Housekeeping was so edgy?)

The Vice screed, by Michael Easter, leans heavily into the elitist critique, and it also argues that not only are organic foods no better for weight loss (calories being calories), but even the purported health benefits are dubious. (A meta-study concluded that organic foods are not significantly more nutritious than their counterparts, but they “may reduce exposure to pesticide residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria.”) “There are, of course, plenty of valid reasons for supporting clean foods,” Easter states, “ranging from concern over the treatment of animals to supporting local farmers. But those concerns have nothing to do with health and weight loss, clean eating’s big sales pitch.”

Nutritionist Jaclyn London in Good Housekeeping also calls out the elitism: “The implication is that if you’re not ‘eating clean,’ what you eat otherwise is dirty, lazy, or unhygienic, and that’s simply not true.” And as for benefits: “More and more marketers refer to their food products as ‘clean.’ But if your product is 90% full of a trendy version of oil or sugar, it’s still not providing consumers with healthful, educated choices. Don’t believe me? Agave is no better for you than any other version of sugar; coconut oil is still a mostly saturated fat (even when your kale salad is doused in it); cold-pressed juice is still a concentrated source of sugar (and not very nutritious); and that vegan chocolate pudding is still dessert—not breakfast.”

Bee Wilson’s “Why We Fell for Clean Eating” in The Guardian goes further, highlighting the consequences of orthorexia—an unhealthy obsession with healthy eating, a relentless pursuit of food “purity” which can cause extreme anxiety and nutrient deficiencies or excesses. “‘Clean eating’ was different,” Wilson writes, “because it established itself as a challenge to mainstream ways of eating, and its wild popularity over the past five years has enabled it to move far beyond the fringes. Powered by social media, it has been more absolutist in its claims and more popular in its reach than any previous school of modern nutrition advice….[I]t quickly became clear that ‘clean eating’ was more than a diet, it was a belief system, which propagated the idea that the way most people eat is not simply fattening, but impure.”

CLEAN EATING: THE ORIGINAL

This has all gotten way out of hand. A bodybuilding term which meant simply eating lean as opposed to eating junk has now been marketed and hashtagged into a catch-all word for organic, natural, and, often, vegan. Clean food has gone from literal to slang to literal again, so that most people now treat the term as a reflection of actual cleanliness, of a sort—no chemicals, no processing, often no animal products—a synonym for purity.

It’s probably too late in the #eatclean era to turn back the clock. Still, the meaning never altered in the muscular community from which clean came. It still means eating lean protein, complex carbs, and veggies (whether or not they’re organic) and, in order to better reveal abs, avoiding things like white flour, sugar, and saturated fat (even if the foods laden with them are marketed as “organic,” “all-natural,” “pure,” or “clean,” or they’re sold at Panera Bread, Tender Greens, or Whole Foods Market).

“Eating clean” is eating to lose or minimize bodyfat.

Its antonym, “eating dirty” is pizza cheat day.

If the world outside our gyms is going to keep running with that other squishy meaning with its overreaching claims, that’s up to them. But like “shredded,” “natty,” “dialed in,” and “freak,” “eating clean” will mean what it’s always meant in the bodybuilding subculture, and if that confuses the uninitiated, so be it. Either you’re in or you’re out.